The realm of video games as we know them today is rooted deeply in a history of innovation that predates digital graphics and CPUs. Before the era of digital screens and video game consoles, there was a fascinating world of electro-mechanical games. These games, which included pinball machines and various coin-operated attractions, were purely mechanical in their operation and did not incorporate screens. Manufacturers like Nintendo, Taito, and Sega initially started with these types of games before moving into the digital gaming space.

A notable pioneer in this area was Sega, which produced its first electro-mechanical game, "Missile," back in 1969. This game presented a missile defense scenario using intricate dioramas, mirrors, and lights to create the gaming experience, a method quite common in the electro-mechanical gaming era. The gameplay, devoid of any digital components, relied on players' physical interactions with the game machine.

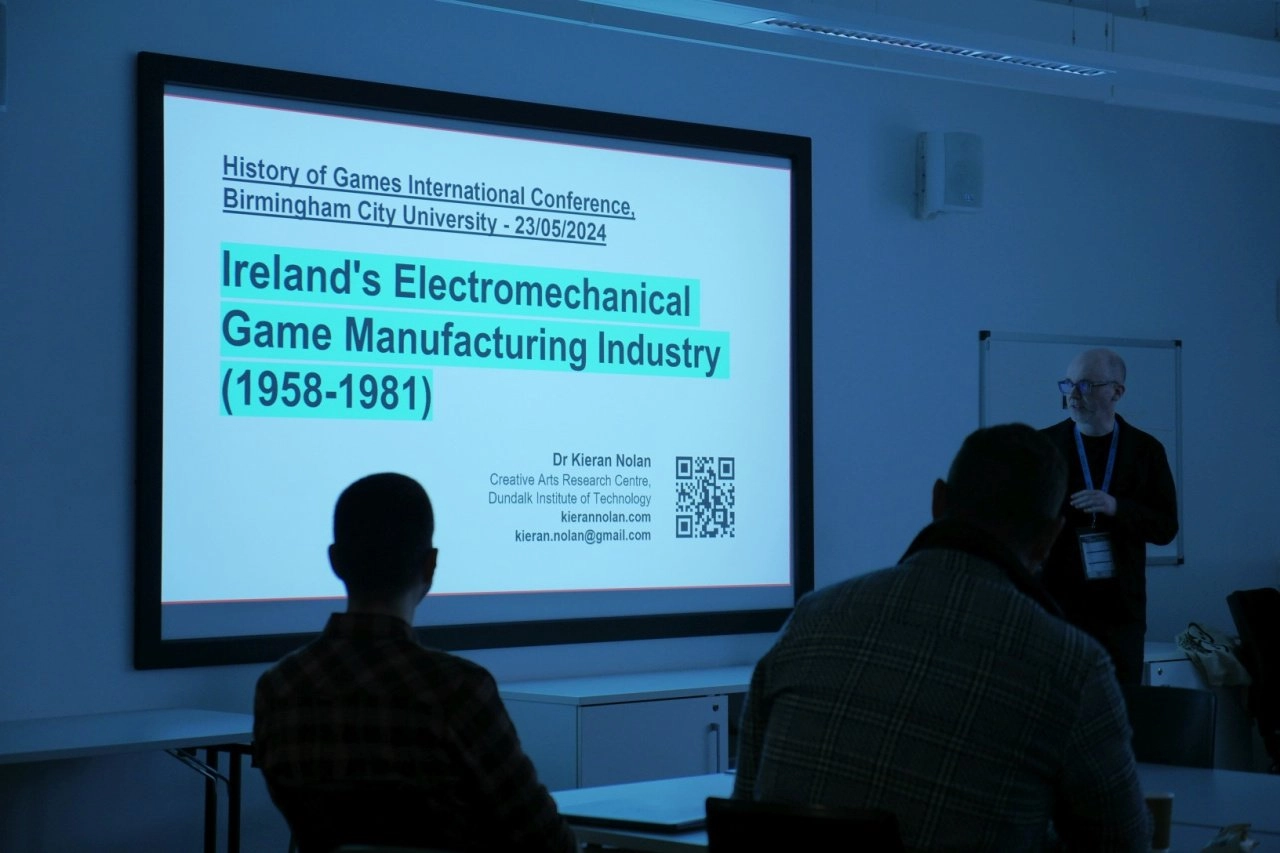

The fascination with these mechanically operated games wasn't limited to Japan or the United States. Ireland, although not typically recognized in the gaming world, has an intriguing history with arcade games as well. During a recent History of Games 2024 conference, Dr. Kieran Nolan revealed Ireland's contributions to this industry. He detailed how companies like Mondial and Bally established operations in Ireland during the late 1950s and 1960s, thereby weaving Ireland into the broader narrative of global arcade game production.

Mondial set up its base in Dublin in 1958, functioning primarily as an importer and assembler for major pinball manufacturers like Gottlieb and Williams. Supported by the Irish government, Mondial sourced critical components from the United States and assembled the machines locally, contributing significantly to the local economy and job creation. At its peak, the company produced approximately 50 games per week, a testament to the booming interest and market for these mechanical games.

Similarly, Bally opened its facilities in Dublin in 1965, and another company, IDI/Co-Am-Co, was established in Shannon in 1959. These establishments not only boosted Ireland’s economy but also played pivotal roles in the evolution and spreading of arcade culture within Europe. Despite their successes, these operations faced challenges, including labor disputes over safety issues in workplaces, which highlighted the growing pains of an evolving industry.

Dr. Nolan’s research, which delves into local newspaper archives and attempts to interview individuals involved during that era, paints a picture of a time when Ireland was more than just a scenic travel destination; it was a hub for mechanical innovation in entertainment. Though much of the physical documentation and corporate records of these companies have mysteriously disappeared over the years, the stories that remain offer a fascinating glimpse into a lesser-known chapter of technology and culture.

Interestingly, this segment of Ireland’s economic history pre-dates the more widely recognized Celtic Tiger era, during which Ireland experienced rapid economic growth. The mechanical game manufacturing industry thus serves as a precursor to the later technological advancements that would shape Ireland's economic landscape. These initial forays into mechanical gaming underscored the country's capability and ingenuity, setting the stage for future technological endeavors.

Dr. Nolan’s ongoing research and commitment to uncovering more about Ireland’s role in the early game development scene is crucial. It not only enriches our understanding of the global history of video games but also highlights the cultural intersections of technology, entertainment, and economics. By examining these beginnings, we can appreciate the evolutionary journey from mechanical arcades to the digital gaming powerhouses we recognize today. Dr. Nolan plans to expand this research, promising further exploration into Ireland’s forgotten arcade history. Such work is essential, as it not just recovers lost chapters of our past, but also informs future innovations in the gaming industry.

You must be logged in to post a comment!